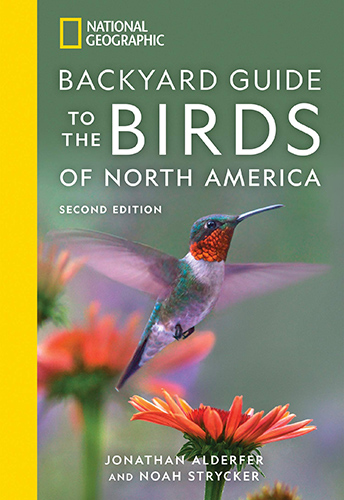

THE BACKYARD GUIDE

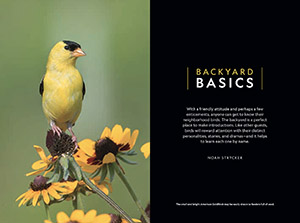

Co-authored with Jonathan Alderfer, this completely revised second edition of National Geographic’s popular guide describes 150 of the most common backyard birds in North America. This book can help anyone appreciate and identify the feathered friends outside their window, and it gives tips on birdhouses, feeders, landscaping, and other attractions. A perennial top seller among field guides, the Backyard Guide is packed with useful information about the birds in our midst.

See 2,000+ ratings (4.8 stars) for this book on Amazon

EXCERPTS: Click any heading to read a tidbit from the book.

How Do Chickadees Survive Winter?

How Do Chickadees Survive Winter?

In the frostiest depths of January, a few birds stick around to keep backyard birders company. If you’re lucky, and keep a feeder stocked, these all-weather friends might include chickadees.

Even in parts of North America where the temperature plunges to 40 degrees below zero, chickadees keep a steady presence. How can a bird that weighs less than half an ounce endure such frigid conditions?

Their size is a definite disadvantage. Tiny birds have a high ratio of surface area to volume, which means they lose more heat than bigger birds, for the same reason that small ice cubes melt faster than big ones.

Bearing The Cold

Chickadees have developed special strategies for the cold. They spend winter nights tucked in narrow cavities, sometimes huddling together for warmth with downy feathers fluffed out. These crevices are typically smaller, and cozier, than a summer nest hole.

Black-capped Chickadees in northern regions enter torpor on chilly nights, cooling their body temperature from about 107°F (42°C)—hotter than a human—to below 90°F (32°C). This saves a significant amount of metabolic energy.

Fueling Up

Chickadees still must eat—a lot—to stay warm. A chickadee can consume 60 percent of its body weight each day in seeds and insects, putting on 10 percent of its weight in fat by dusk. That extra fuel is burned overnight, as if a 150-pound human slept outside and woke up 15 pounds lighter.

For the sake of the chickadees, keep those winter feeders full.

Watching Sparrows

Watching Sparrows

Many bird-watchers pass off sparrows at LBJs—”little brown jobs”—but don’t discount this fascinating group of birds. Like an Italian sports car, sparrows reward a lingering, subtle sense of appreciation.

Can anything, after all, be as crisp as the profile of a White-throated Sparrow? Take a good look at those lines, like racing stripes, accented by the little yellow flame in front of each eye. There’s a paint job straight from Formula One.

Or consider the Song Sparrow, with its brushed underparts, reminiscent of Monet’s field of haystacks. The bird in canvas in motion, each feather its own work of art.

Identifying sparrows is not for dilettantes; the only difference between an expert bird-watcher and a novice is that an expert has misidentified more of these birds. Anyone—expert or novice—can appreciate the aesthetics of a bird as intricately patterned as a Fabergé egg. The closer you look, the more you see.

Music To Your Ears

Don’t forget to listen. In winter, each sparrow has a distinctive call note, packing its whole identity into a single syllable. The best sparrow listeners can separate species by tone, as if picking out a Stradivarius. Then, in spring, these diminutive birds suddenly tilt their heads back and sing, filling field and forest with cascading melodies. Is it language or music? Yes, it is both.

The Fall Of A Sparrow

Even Shakespeare couldn’t resist a bit of sparrowy nuance. “There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow,” quips Hamlet before a duel, musing on his own impending fate. The Prince of Denmark was probably referring to a House Sparrow—but, lacking details, we’ll just never know.

Understanding Cowbirds

Understanding Cowbirds

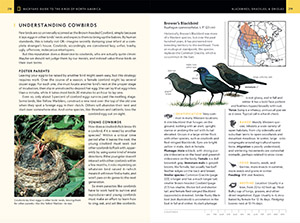

Few birds are so universally scorned as the Brown-headed Cowbird, simply because it lays eggs in other birds’ nests and expects them to bring up the babies. By human standards, this is totally not OK—imagine secretly dumping your infant at a complete stranger’s house. Cowbirds, accordingly, are considered lazy, unfair, trashy, ugly, offensive, indecorous interlopers.

But this reputation does a disservice to cowbirds, who are actually quite clever. Maybe we should not judge them by our morals, and instead value these birds on their own terms.

Foster Parents

Leaving your egg to be raised by another bird might seem easy, but this strategy requires work. Over the course of a season, a female cowbird might lay several dozen eggs. For each one, she must locate another bird’s nest at the proper stage of incubation, then slip in unnoticed to deposit her egg. She can lay that egg in less than a minute, while it takes most birds 20 minutes to an hour to lay one.

Even so, only about 3 percent of cowbird eggs survive past the nestling stage. Some birds, like Yellow Warblers, construct a new nest over the top of the old one when they spot a foreign egg in their clutch. Others will abandon their nest and start over somewhere else. And some species, like thrashers and catbirds, toss the cowbird egg out on sight.

Young Cowbirds

How does a cowbird chick know it’s a cowbird, if it is raised by another species? Within a critical time period after it leaves the nest, the young cowbird must seek out other cowbirds to flock with, apparently by using some kind of innate directions. If the youngster doesn’t interact with other cowbirds within a few months, it risks imprinting on whatever bird raised it—which means it will never find a mate, and won’t pass on its genes to the next generation.

So even parasites like cowbirds have to work hard to survive and reproduce—and young cowbirds must make an effort to learn how to sing, eat, and act like cowbirds.

Why Don’t Woodpeckers Get Headaches?

Why Don’t Woodpeckers Get Headaches?

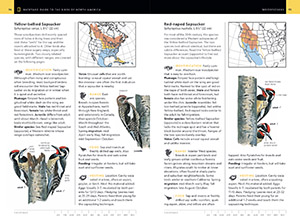

Woodpeckers are so called due to their headbanging behavior against immovable objects. Woodpeckers “drum” and peck to find insect prey, to make cavities for nesting and roosting, and to communicate with other woodpeckers. During the courtship season, when males drum against resonant trees or rain gutters to attract mates, a healthy woodpecker may peck thousands of times a day (females may also drum briefly to announce themselves in a male’s territory). The thought of it makes one’s head hurt. How to the birds avoid constant concussion?

Extra Padding

Strong muscles in a woodpecker’s head and neck help cushion against impact while preventing whiplash. The birds’ anatomy has been studied for inspiration in football helmet designs, which aim to do the same thing.

But these peckers have some other tricks up their beaks. Their upper nostril connects to a thin bone called the hyoid, which in woodpeckers has elongated so that it wraps all the way between the eyes, over the top of the skull, and around the back of the head. At the base of the skull, the tongue attaches to the end of this bone.

The hyoid acts like a seat belt, contracting and tightening around the brain to dampen force. It also diverts shock vibrations away from the cranium: Because a woodpecker’s upper beak is slightly longer than the lower, the forces of impact travel first through the upper nostril into the hyoid, which helps dissipate energy into other muscles, including the tongue.

Eyes Closed

A millisecond before striking, a woodpecker blinks its third eyelid, called the nictitating membrane, which shuts from the front to the back. This eyelid, present in most bird species, helps protect and moisturize. For a woodpecker, the benefits are obvious: With the eyelids closed, a woodpecker doesn’t get flying wood chips in its eyeballs, and its eyes don’t pop out on impact. And because this membrane is translucent, the bird can still see where it’s pecking.

Robin Egg Blue

Robin Egg Blue

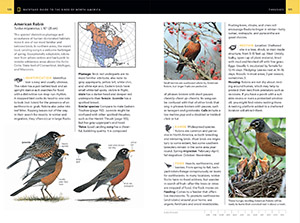

Bird eggs come in all hues and patterns: brown, white, cream, red, green, speckled, and spattered. The eggs of ground-nesting birds are remarkably well camouflaged against their surroundings. But other colors are harder to explain. Why, for instance, does the American Robin lay bright blue eggs?

Across their range, robins build a cup-shaped nest of straw and mud. The female usually produces four ummarked eggs, in a beautiful shade very similar to Tiffany Blue—the cyan color trademarked by New York City’s high-end jewelry company. Scientists have struggled to explain why a bird would lay such conspicuously colorful eggs.

A Healthy Family

One interesting study showed that male robins take better care of chicks that hatch from brighter-colored eggs. In an egg-switching experiment, robins were given either dull blue or neon blue eggs to incubate. After hatching, the male parents with bright eggs fed their chicks twice as much as those with dull-colored ones.

Researchers theorized that egg color helps gauge the mother’s fitness, and that males are more motivated to take care of chicks they believe are healthy.

Natural Sunscreen

Another possibility is that blue eggs are a trade-off for sun exposure. Light-colored eggs transmit more harmful ultraviolet rays to the embryo inside, while dark-colored eggs heat up faster in the sun (what researchers have called the “dark car effect”). For a bird that nests in dappled shade, like a robin, a medium color could balance the two extremes.

But that doesn’t explain why some cavity-nesting birds, like Eastern Bluebirds, also lay blue eggs. You’d think sun protection would be unnecessary in a dark hole. This is a good question to ponder while gazing into the sky on a cloudless day: Why is a robin’s egg blue?

HOW TO ORDER

The Backyard Guide to Birds of North America is available through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other booksellers.