INTRODUCTION

Imagine what might happen if birds studied us.

Which human traits would catch their interest? How would they draw conclusions?

Perhaps birds would begin, as most good scientists do, with the basics. They could spend a lot of time measuring the human body: weight, height, strength, pulse, brain size, lung capacity, color, growth rate, life expectancy, and so on. Academically minded birds could fill volumes with clinical, physical observations of people. Of course, they’d have to dispatch teams of field techs to collect the data. You might step out your front door one morning to find yourself entangled in an invisible net, surrounded by efficient young robins armed with rulers and scales. No doubt they’d soon send you on your way, none the worse for wear save the embarrassment of being caught and the loss of a few carefully plucked strands of hair. Then the robins would retreat to analyze their numbers.

How much could a bird really get to know us from these physical statistics? Take brain size, the feature we humans tend to be most proud of. A bird might rightly point out that, for sheer size, the human brain is nothing special; whale and elephant brains, for instance, are much larger. Birds could go a step further and compare human brain size to body weight, but even then, humans wouldn’t stand out: Our ratio of brain to body weight is about the same as that of a mouse (about 1/40) and is smaller than that of some birds (1/14); in terms of relative size, ants may have the biggest brains of all (1/7). To explain these mediocre numbers, humans have observed that, while brain size increases along with body weight, it follows a power law—in other words, brains don’t increase in direct proportion to bodies. But this formula was developed by mammals, for mammals. Birds, if they were to study our brains, might not embrace this logic. They might not think that the human brain—or the human animal, for that matter—was particularly interesting.

To really learn about humans, curious birds would therefore have to study more than just our bodies. They would have to closely observe how we behave, and then try to figure out why we act in the ways that we do—a monumental task. Consider the deceptively simple question: Why are you reading this book? You might say, “to learn about birds” or “for entertainment,” but your reasons probably go beyond that. Reading seems to fulfill a widespread human urge. Evolutionary biologists point out that people of many cultures enjoy reading despite the fact that, for most of human history, writing didn’t exist. Deciphering words on a page must take advantage of abilities that have been hardwired into us, but nobody quite knows why we like to read. And if we don’t know why we do it, what could a bird possibly make of you reading this book? How would a bird draw conclusions about a behavior so foreign to its own?

If birds set out to study human behavior, they’d almost certainly start with something familiar to them. They could, for instance, study our sleep habits. That team of robin field techs would camp out in a corner of your bedroom, making detailed notes about things like the color of your bed sheets and the volume of your snores. Surely birds would understand the need to rest each night. But what would they conclude about the wider human condition from these bedroom vigils, especially considering that birds don’t sleep the same way we do? Most birds are very light sleepers, rarely falling into the same dead-to-the-world state so familiar to people. And a few birds have particularly strange sleep habits—some swifts are thought to sleep on the wing, perhaps with half their brain turned off at a time. There is a type of parrot that sleeps hanging upside down, like a bat. Hummingbirds enter a state of near-death torpor after dark to conserve energy. Even the most basic behaviors, like sleep, become more complex the more they are studied—and more difficult to understand.

From their research of human habits, birds might even conclude that people wish they were birds. Think of the trillions we have spent on airplanes, space shuttles, and other flying machines over the past century. What is a bird to think? Would they argue over the differences between bird and human behavior—and whether those differences are absolute or merely a matter of degree, as Darwin once suggested? A bird might examine one of our airplanes with pity, and feel superior to its human study subjects. Who could blame it?

*****

The idea of birds studying people is pure anthropomorphism—assigning human characteristics to birds just to make a point. Birds have better things to do than study humans, and it’s debatable whether they even have the mental capacity to comprehend concepts like scientific inquiry. Birdwatchers often joke about birds watching them, but birds probably don’t nurture much interest in us beyond a basic fear of predators (check out the chapter Fight or Flight: What penguins are afraid of for more about this). We play only a minor role in the bird world.

And yet, the more that humans study birds and discover more about their behaviors, the more similarities we find between ourselves and our feathered friends. In almost any realm of bird behavior—reproduction, populations, movements, daily rhythms, communication, navigation, intelligence, and so on—there are deep and meaningful parallels with our own. A recent shift in scientific thinking about animal behavior encourages us to concentrate less on the uniqueness of humans and more on what the human animal shares with other animals. Traditionally human characteristics like dancing to music (see the chapter Beat Generation: Dancing parrots and our strange love of music), recognizing one’s reflection and sense of self (Magpie in the Mirror: Reflections on avian self-awareness), creating art (Arts and Craftiness: The aesthetics of bowerbird seduction), and even love and romance (Wandering Hearts: The tricky question of albatross love) are now recognized in birds. This isn’t anthropomorphism at all; anyone who suggests otherwise is ignoring a large part of what it means to be a bird. Moreover, a wave of neurological research on people indicates that the same behaviors, when expressed in humans, may be more instinctive than many of us realize, the result of eons of natural selection—behaviors that evolved, in other words, because they give us a survival advantage. So the perceived gap between humans and other animals has lately been shrinking at both ends.

I have been fortunate to spend much of the past decade in the field, working on hands-on research projects with scientists studying bird behavior. These projects have allowed me to spend months at a time watching birds in some of the world’s most remote places: the Ecuadorian Amazon, a penguin colony in Antarctica, the Australian outback, California’s Farallon Islands, Costa Rican and Panamanian jungles, the Galapagos Islands, the Falkland Islands, remote islands in Maine, Hawaii’s Big Island, and others. I’ve observed nearly 2,500 species of birds with the ever-growing realization that they are not our subjects, but rather lively, unpredictable individuals loaded with personality and spirit. It takes time to get to know birds, as it takes time to get to know anyone.

Some bird behaviors don’t apply to humans, and those are especially fascinating and exotic: a “sixth” magnetic sense (Fly Away Home: How pigeons get around), flocks that operate as magnets (Spontaneous Order: The curious magnetism of starling flocks), and the smelling power of Turkey Vultures (The Buzzard’s Nostril: Sniffing out a Turkey Vulture’s talents). It’s hard to imagine having such superpowers, though birds sometimes inspire us to try.

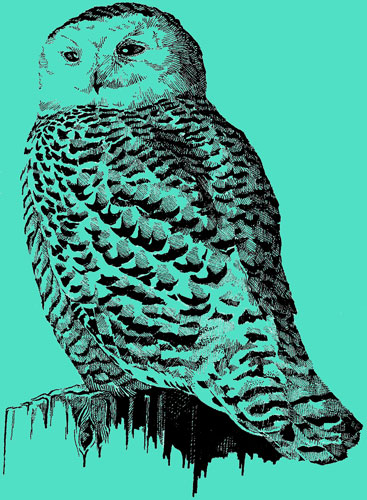

But, if you look closely enough, many seemingly incredible bird feats have human counterparts, with interesting lessons. Cooperative nesting in fairy-wrens (Fairy Helpers: When cooperation is just a game) helps illustrate why humans are usually nice to each other. The dazzling speed of hummingbirds (Hummingbird Wars: Implications of flight in the fast lane) serves as a warning about our own quickening pace of life. Snowy Owls (Snow Flurries: Owls, invasions, and wanderlust) confirm that not all who wander are lost. Even the domestic chicken (Seeing Red: When the pecking order breaks down) has something to teach us about the natural pecking order.

This book may be about the bird world, but it’s also about the human world. Birds can behave in curious, flashy, and startling ways, but they seek the same basic things we do: food, shelter, territory, safety, companionship, a legacy. Each of these chapters explores a compelling bird behavior and focuses on a bird that embodies it. Here you’ll read one amazing bird story after another. Prepare to be blown away by, for example, the memory of Clark’s Nutcrackers (Cache Memory: How nutcrackers hoard information), which show us what the brain is capable of, and might inspire us to boost our own brainpower.

By studying birds, we ultimately learn about ourselves. Bird behavior offers a mirror in which we can reflect on human behavior. In The Thing with Feathers, the mirror is all around, glinting from the wingtips of hundreds of billions of the 10,000 species of birds that share this planet with us. Lucky for us, birds are everywhere. All we have to do is watch.